Bill Coore spends weeks tramping around a work site. He always wears hiking boots; occasionally, if the underbrush is thick or thorny, he dons chaps. On a new project, his first task is to identify the easiest, most natural ways to move around the land, often guided by the paths that deer and other native animals have created.

Bill Coore is considered one of the most visionary golf course designers in the world. He takes WSJ on a tour of his newest, Streamsong, in Florida, and talks about what goes into designing a challenging, rewarding course.

Mr. Coore designs golf courses, but typically not the kind of intensively manicured, cookie-cutter courses that most people are familiar with. Mr. Coore is a “minimalist” golf designer. With his partner and two-time Masters champ Ben Crenshaw, he has laid out and overseen construction of many of the most highly regarded U.S. courses built in the last 20 years.

“Even if most golfers will eventually be taking carts, the route the course takes through the land should seem natural, aligned with how they would instinctively traverse the land if they were on foot,” he said.

For Mr. Coore, 66, and Mr. Crenshaw, 60, the site is at the heart of their creative vision. Instead of bulldozing landscapes, they look for sites that are “naturally gifted for golf,” in Mr. Coore’s words. Then they will move as little dirt as possible in crafting the finished product. Construction itself, including turf grow-in, usually takes a couple of years. The architects’ fees can be a million dollars or more.

“The human capability for imagination is vast, but it’s nowhere near as vast as nature’s in terms of variety, randomness and surprise,” he said. A good course, he believes, will fit seamlessly into the landforms the site provides. The partners’ masterpiece, Sand Hills near tiny Mullen, Neb., snuggles into the treeless dunes that surround it almost indistinguishably, except for the closely mowed greens and tee boxes. The unique challenges of each hole—how far a drive must carry, the best entrance angle into a green—flow directly from the particular features of the landscape upon which it is built. Golfweek has consistently rated Sand Hills No. 1 on its list of modern American courses (those built since 1960). Messrs. Coore and Crenshaw have built similarly admired courses on the rugged Oregon cost, a cliff overlooking Long Island Sound in New York and in the Arizona desert.

Mr. Coore, who briefly played college golf at Wake Forest, got his start as a construction and design aide to Pete Dye, the architect behind such famous courses as TPC Sawgrass in Florida and Whistling Straits in Wisconsin. He teamed up with Mr. Crenshaw in 1985.

When the site for a new project is offered, Mr. Coore will spend several days walking the land, sometimes on multiple visits. So will Mr. Crenshaw, who still competes on the PGA Tour’s Champions Tour (and is playing at this week’s Masters). “It’s a very nebulous process. Do I see contours that suggest interesting golf shots? Do a few natural locations for greens, or even entire holes, pop out at me?” Mr. Coore said. He’s also on the lookout for potential dead ends: ridges or environmentally restricted wetlands that might disrupt the natural progression of holes. In some cases Messrs. Coore and Crenshaw recognize a site’s potential but recommend to the developer other architects whose more traditional styles might be more suited to it. “Ben and I are so aligned philosophically that we seldom disagree about which projects to undertake,” Mr. Coore said.

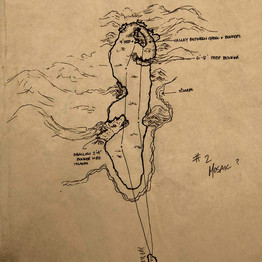

This drawing shows two ways that a player might approach the hole. The landscape’s features force a choice.

Once committed, Mr. Coore (on some visits with Mr. Crenshaw, on others without) may spend weeks defining the overall circulation pattern. Then he starts working with topographical maps and aerial photos of the site to chart particular holes. “Best of all is a topo map superimposed over an aerial,” he said. Working in the field, he folds the maps to show the relevant section and uses a Sharpie pen to make arrows and notes about “interesting spots” that might become greens or fairways. His only other tools are a 12-inch ruler and a range finder that Mr. Crenshaw purchased in the 1980s. “It’s so big it looks like World War II binoculars, but I like it. You need exact distances because the vegetation will play tricks on you, visually,” he said. As work progresses, he or assistants will begin to cut larger paths through the site using machetes, chain saws or small Bobcat earthmovers.

Back in the construction trailer, or in his hotel room, Mr. Coore will study each day’s map and combine the day’s ideas and insights onto master maps. “We are still old-school. We don’t do anything with CAD systems or computer programs. We’re like the lumbering dinosaurs just prior to extinction, but somehow we get away with it,” he said.

Topographical lines superimposed on an aerial image help Mr. Coore to piece together a course like a jigsaw puzzle.

Mr. Coore eschews high-tech tools in part because he believes that building courses is more art than science. At Sand Hills, the dunes were so similar to each other that it was hard to distinguish them on a topo map. So he skipped the maps. Working closely with his “shapers”—experts at creating the slopes and contours of greens, fairways and bunkers with bulldozers, shovels and rakes—he and his partner laid out the course by the seat of their pants.

Even after holes and greens are roughed in, they continue to evolve. Over the years, Messrs. Coore and Crenshaw—who work from offices in Arizona and Texas, respectively—have come to know each other so well that they almost seem telepathic in their communication, not just with each other but with the loyal crew of shapers and construction managers they use on all their projects. In February, for example, Mr. Coore spent three days walking the fairways at his latest project, Streamsong in Central Florida, with his associate Keith Rhebb. A third of the fairways had yet to be grassed, but as they stood in one, looking toward the green, Mr. Coore pointed out how the mounds next to two fairway bunkers appeared, from that vantage, to be the same height, even though one bunker was 40 yards more distant than the other. “They look squared off. Players won’t get the right perspective from here,” he told Mr. Rhebb. Mr. Rhebb proposed reducing the height of the closer bunker, and Mr. Coore agreed.

In the year-and-a-half-long construction process at Streamsong, Mr. Coore and his team have made scores of similarly subtle tweaks, from adding 2-inch-high undulations to a putting surface to reorienting a fairway so that the distant peak of a dune can serve as an aiming point. The best courses work on many levels, including subconsciously. “It’s like a really good essay or poem,” he said. “If you get all nuances the first time through, well then, it wasn’t very good.”