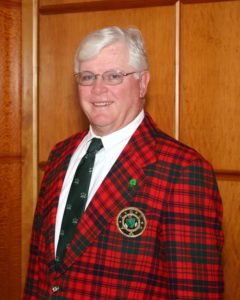

Bob Cupp served as senior designer for Jack Nicklaus for fifteen years before forming Cupp Design, Inc. in 1984. He served on the board of directors of the American Society of Golf Course Architects. He also authored the acclaimed book, The Edict: A Novel from the Beginnings of Golf. His golf course design work includes Cloud 9 at Ghost Creek and Witch Hollow at Pumpkin Ridge Golf Club; Angel Park in Las Vegas; The Club at Savannah Harbor, Crosswater at Sunriver Resort; Old Waverly; Emerald Bay in Destin; Indianwood Country Club’s New Course; the Plantation Course at Reynolds Plantation; Star Pass Resort in Tucson; and Shadow Wood Country Club in Bonita Springs.

Bob Cupp served as senior designer for Jack Nicklaus for fifteen years before forming Cupp Design, Inc. in 1984. He served on the board of directors of the American Society of Golf Course Architects. He also authored the acclaimed book, The Edict: A Novel from the Beginnings of Golf. His golf course design work includes Cloud 9 at Ghost Creek and Witch Hollow at Pumpkin Ridge Golf Club; Angel Park in Las Vegas; The Club at Savannah Harbor, Crosswater at Sunriver Resort; Old Waverly; Emerald Bay in Destin; Indianwood Country Club’s New Course; the Plantation Course at Reynolds Plantation; Star Pass Resort in Tucson; and Shadow Wood Country Club in Bonita Springs.

It was one of those March days in south Florida when the wind gusted in unpredictable blasts up to thirty miles an hour, testing every player in an obscure PGA event conducted each month by the South Florida Section at one of the member clubs, which were always closed on Mondays. The players (local club pros, their assistants, and a few wintertime visitors) threw fifty dollars in the pot and competed for the prize. It was a time for newcomers to make their mark or for the old hands to prove they still could.

In 1967 I was still several years short of thirty, an assistant club pro as obscure as the event in which I placed my money; precious dollars in those days, but that particular fifty, it turned out, would buy me a glimpse of my future – or perhaps more accurately, an honest look at a spotted past that was about to come to a close.

Less than a year prior, I had held a relatively good position as an art director for an advertising agency into which I followed my education and stated goals for life. Unfortunately, I had hit a wall. A year and a half into my directorship, creativity had become my pariah. The evolving emotional upheaval was ostensibly an early mid-life crisis or, perhaps, just sheer boredom. As far back as memory served, creativity had always fueled my psyche. When I took that job after my military commitment was complete, I discovered that creativity-on-demand was no longer fun. The spontaneity, variety, and freedom evaporated in the neckties, blazers and starched shirts, and it was a crisis of the first order.

But I was still young enough to be bulletproof. Quite accidentally, I fell upon an opportunity to produce an advertising program for a man who owned a small golf course – a strange, diminutive character with a shifty glance that belied his otherwise honorable (I would later discover) character. The marketing “package” was primarily composed of a series of newspaper ads, which, for all intents and purposes, was the volume merchandising of golf equipment at discount prices. He asked my fee and I blithely responded, in my most professional manner, “One percent of the gross increase of business – and, since I really need to understand the golf industry, playing privileges.” The latter, of course, was the hook, and I said it in dead earnest. All I wanted was free golf. We wrote a simple agreement.

I know he believed an ad might have a lot of value because he told me so many years later. He thought the sales would cover the cost of the ads plus a little. I knew exactly how every element of the ad would work, but was oblivious to its potential. It exploded, driving his inventory from less than $15,000 to over a quarter of a million in less than a year.

Within three months the owner told me he could not afford to pay me the gross percentage because I would be making more money than him, but that if I was interested, he would be happy to hire me to run his growing shop. The following Monday I walked calmly into the office of the senior partner of my firm and said good-bye. Welcome to the golf business.

I continued playing as an amateur with some success because suddenly there was plenty of time to practice – and I had rid myself of my demon. Within the year, a private club offered me a similar position and the new pro suggested I declare my status as a professional. He even allowed me to give a few lessons and put my name on the door below his. In my liberation from “art-on-demand,” the creative urges came back and in the first few months in this exciting new environment I drew a number of adjustments to the course, some new tees, two fairway bunkers, and a new bunker at one of the greens, all of which the pro thought should be presented to the owner.

Now fade to the windy March day at Redlands Country Club, well south of Miami – forking over my hard-earned fifty.

For whatever reasons, the golf that day was easy. I was not distraught over a thirty-seven in the blow on the front nine because it could have been much better, but I was a rookie and nerves had undercut my confidence somewhat. But as we played on, it became obvious that I was doing much better than my two mates – one of the oldsters, a well regarded club pro, and another assistant like me in his third year. I was becoming comfortable.

A birdie on a downwind par-five preceded a four-hole run of bogey-birdie that put me on the sixteenth tee at even par and feeling pretty good, though not bulletproof enough to stave off visions of doubles from there to the house.

But one long putt and two downwind holes enabled me to turn in a seventy-two, to the raised eyebrows of the scorekeeper, which felt especially good.

Little did I know at the time that this would be the apex of my professional playing career. What happened next would change my life.

From the scorer’s table I turned toward the scoreboard. Two seventies met my eye right away, becoming the first twinges of reality. Then I saw a sixty-eight. “Good grief,” I thought, “what kind of animal goes four under on a day like this?”

Then I saw it. There, the last score on the board at the bottom. A sixty-two.

I traced the numbers back to the left; a series of twos and threes, several fours, maybe a five, and the total was not a mistake. My eyes finally reached the name. “Gibby Gilbert! Who ever heard of Gibby Gilbert?” My mind disintegrated into disbelief.

But I would soon learn who Gibby was; within a few years he would win PGA Tour victories at Houston Champions, the Danny Thomas in Memphis, and the Walt Disney World National Team Championship. All in all, he would win ten events plus a record three Tennessee State Open Championships.

But there I was. Having just played what I thought was a great if not brilliant round, and I had been beaten by ten shots. Through the combined astonishment, disappointment, and anger, the forces of the real world settled on my soul. The truth was obvious. I was not good enough for this and could never win. My transformation had begun.

Looking back now, human resilience is amazing. About the time I accepted defeat, my remaining elements had formed into some sort of new alignment. The drawings of tees and bunkers came into focus. They were golf. I loved golf. I could draw. Maybe I couldn’t beat the Gibby Gilberts of the world, but I could draw – so that’s where I had to go. I think I turned away from that looming dark green structure a different person. The transformation was that fast. Just as suddenly, the confidence (or was it wishful thinking?) was coming back. I knew that as soon as it was possible to arrange a meeting with my new boss, I would present those changes to our course.

It was in fact the next day, and again, with the help and support of the head pro, I found myself sitting in an office with my drawings.

“Wow,” said the boss to my surprise. “These look really good. Go do it!”

When the stars actually do align, or if indeed there is a grand plan, I must have been in it. I found the help and did the work to the satisfaction of everyone, followed by a number of other repairs to the course. I received inquiries from other clubs for services, and collaborated with an engineer to do three holes for the Air Force base (then, ludicrously, the remaining six holes) and finally a new eighteen for another developer. I was on my third eighteen and had completed a number of other revisions when I had a call Jack Nicklaus. He called me himself as I sat in my little construction building on the unfinished fourth fairway and I almost fell out of the shack onto the dirt. His voice was unmistakable. Nicklaus wanted to speak with me about his dream of his own independent design company. Over the years I would learn he, too, had a sudden, striking understanding about himself and his love of design. As it turned out, this phone call was about more beginnings; certainly for him and what I know now to be a great source of satisfaction to him. But for me, it was the beginning of the rest of my life.

About thirty years later, when Gibby was inducted into the Tennessee Golf Hall of Fame, we fried him at the banquet with all the humor and honor we could muster. It was fun. I told him this story, up to the point of my epiphany, citing my decision to enter the design world at the instant I saw that sixty-two on the scoreboard – and Gibby’s comment was a classic. “Bob,” he said, “You made the right choice.”