Wall Street Journal took a deep dive below the surface to better understand how golf courses work. Brad Klein includes insight from ASGCA President Jason Straka and reports, “If the soil, root structure, drainage, fertility and chemistry weren’t perfectly tuned down below, the surface will be bumpy, the golf experience frustrating—and the course superintendent will get an earful from players.”

The complete article can be found following and here.

Even for golfers who have played their own home course a thousand times, a familiarity with tee shots, approaches, putting and avoiding hazards is only a small piece of what they really confront. Most of what it takes to make a golf course work is out of sight, buried below that pristine surface.

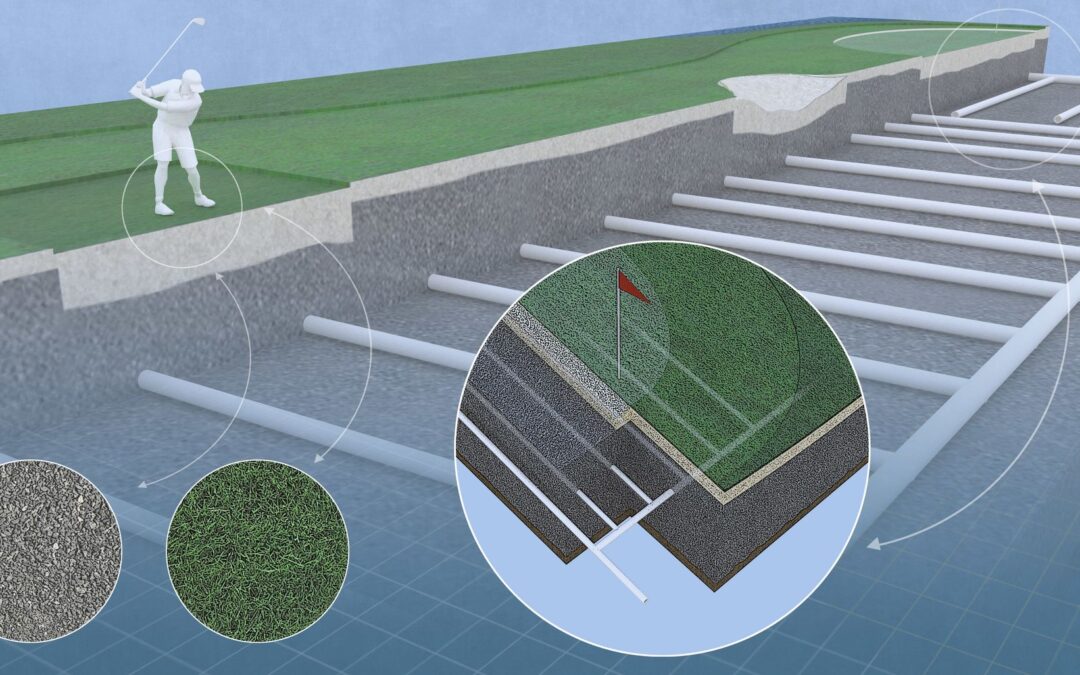

A golf course these days comprises a dense network of infrastructure that makes it possible for the surface palette of material to function well—or not. What shows up to the golfer as a playing field of tightly mowed turf-grass greens, fairways and tees surrounded by taller grass and sand-filled bunkers is just the surface manifestation of the underlying soil, root-zone mix, water chemistry, fertility, irrigation pipe, wire and drainage channels.

That smooth, seemingly flawless carpet of turf grass, cut to one-eighth or even one-tenth of an inch of its life for greens and under a half-inch for fairways? If the soil, root structure, drainage, fertility and chemistry weren’t perfectly tuned down below, the surface will be bumpy, the golf experience frustrating—and the course superintendent will get an earful from players.

“Eighty-five percent of your costs are the stuff underground that nobody sees, not the sexy stuff that everybody is playing and talking about,” says Josh Lewis, who was course superintendent at Chambers Bay in University Place, Wash., for the 2015 U.S. Open and is now a partner in the agronomic consulting firm GH Management Group, Palos Verdes, Calif.

Golf courses vary dramatically in size, soil type, climate and infrastructure needs. According to the National Golf Foundation, of the country’s 15,980 golf courses, 5,544, or 35%, are nine-hole layouts. A standard 18-hole course occupies about 125 acres, with roughly 2 acres of greens, 2 acres of teeing ground, 25 acres of fairway, and another acre and a half of bunkers. The rest of the land comprises a combination of maintained rough, native areas, wetlands, creeks, ponds and woodland, plus the area devoted to clubhouse, parking, driving range and maintenance.

Underlying the intensively cultivated areas of tees, fairways and greens is a dense interlacing of pipe, some to get the water off the course and others to provide irrigation as a supplement to rainfall.

Sand-based courses, such as those at St. Andrews in Scotland or Sand Hills in Mullen, Neb., are blessed with a naturally porous growing medium that allows surface water to infiltrate right through. Most modern courses built inland, on heavier soils, don’t percolate surface water as quickly and need the help of a network of drainage pipe, catch basins and dry sumps to vacate their surface water. A mile or two of perforated drainage for a golf course is standard. In some cases, as with the Carlton Woods Jack Nicklaus course in The Woodlands, Texas, the entire 35 acres of fairway is capped with 8 to 12 inches of sand and outfitted with drainpipe set at 20-foot intervals to pick up the accelerated flow of water downward. The volume of water and its movement through the sand requires 17 miles of perforated drainpipe.

Adding water to a golf course requires its own system of pumps, pipes, valves and nozzles—all of it out of sight to players, except for the irrigation heads scattered around the golf course. Roy Wilson, president of the irrigation division of Landscapes Unlimited LLC in Omaha, Neb., a golf-course construction firm, estimates that a standard irrigation system for an 18-hole course runs about $2.5 million and includes 1,400 sprinkler heads, 22 miles of pipe and 26 miles of electrical wire.

All putting surfaces sit on a complex structure of soil that has to provide fertility while allowing enough space for air to get in and water to get out. Older greens, typically those built before World War II, were essentially native soil, sometimes with drainage channels cut into the base. In recent decades green construction has gotten far more sophisticated and technically demanding, with the surface of the green underlaid by more than a foot of sand, as well as a layer of small porous rock and then drainage pipes cut into channels 10 to 12 feet apart that provide an outlet for the water as it seeps through the surface.

A few large-budget courses such as Augusta National Golf Club in Georgia, Winged Foot Golf Club in Mamaroneck, N.Y., and Oakland Hills Country Club South Course in Birmingham, Mich., have gone further, installing mechanized units in underground vaults adjoining the greens that control the moisture level just below the putting surface or the soil temperature of the greens through heating and cooling.

When it comes to convincing a club’s membership to invest in infrastructure, it can be difficult to get them to commit to paying for something they don’t see. Golf-course architect Jason Straka invokes the imagery of a house to explain that a course’s basic components have a shelf life: “Every 10 to 30 years, you have to deal with the roof, furnace, appliances, or air conditioning. You have to fit them into your budget. A golf course is no different.”

Renovating a golf course—which is where most work for course architects is these days—is like going on an archaeological dig: It involves uncovering layers of infrastructure in order to rebuild or replace it. Sometimes that means going deep down into the dirt, uncovering three or four levels of an old putting surface to get to the underlying core.

That’s what Mr. Straka’s team is doing in the restoration of Belleair Country Club’s West Course in Florida, a 1915 design by a legendary figure in golf-course architecture, Donald Ross.

“We’re going down to the original Ross putting surface that had been buried over the years,” Mr. Straka says. “We’re removing 2 feet of a gravel blanket that was restricting the drainage. With one green there, we went down to the old railroad trestle the original green was built upon.”